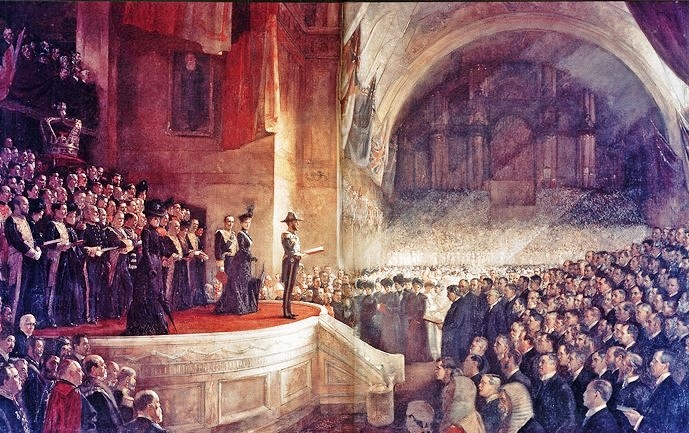

[The opening of Australia’s first parliament by Tom Roberts]

[The opening of Australia’s first parliament by Tom Roberts]

Last week I gave a brief outline of how the Westminster parliamentary system evolved in England. Then came Australia which largely adopted the British parliamentary system and recognised the British monarch as head of state.

I won’t bother with the colonial era, although it doubtless had some influence, but will focus on Australia’s federation in 1901 and the foundation of our system,

The Constitution, as passed by the British parliament and assented to by Queen Victoria. It drew on both the British and American systems: the Senate in particular is based on the US Senate. It seemed to be a given, following the British model, that we should have two houses of parliament but, without ‘lords’ to make an upper house, the American model was adopted to create a ‘states’ house. In reality, it was not essential to have an upper house — New Zealand is governed without one. The difference was that we were federating six separate colonies whereas New Zealand was a single colony. (Our constitution allows for New Zealand to become a state of Australia.) The smaller states supported the American concept of an upper house in which they could not be outvoted by the more populous states of NSW and Victoria. That is also reflected in the provisions for the passing of referenda to alter the constitution: that they must be supported not only by an overall majority of votes, but by a majority of votes in a majority of states — which meant the constitution could not, and cannot, be changed just by the sheer weight of numbers in NSW and Victoria.

Despite the fact that the Westminster system fuses the legislature and the executive, by selecting the ministers from the legislature, our constitution does set out the three arms of government: the parliament (legislature), the executive and the judiciary. It is important that they appear in that order: you may think that the executive should come first, being at the top of the tree, but that obviously wasn’t they way the framers of our constitution saw it —

parliament is supreme, not the executive. On the other hand, the part referring to the Senate does precede that of the House of Representatives, reflecting the traditional style that the upper house is more important. It may no longer be so in practice but it does retain that final right of turning a Bill into an Act before it is presented for royal assent. And the monarch, or the Governor-General, still appears in the Senate, not the House of Representatives, when he/she attends parliament (just as the Queen attends the Lords, not the Commons, in the UK).

I won’t dwell on the chapter regarding the judiciary as that basically establishes the High Court to adjudicate on the constitution (and a few other matters), and the capacity to establish other federal courts. Like the parliament, many of the practices we attach to the judicial system are also a result of hundreds of years of evolution. Thus, although it is not spelled out in the constitution, we expect that only a court can impose punishment because only a court can rule whether or not a law has actually been breached. The constitution, however, does specify

trial by jury when a commonwealth law is broken — and the case can be tried in a state court in the state in which the offence occurred.

Legally, the parliament comprises the monarch (or the Governor-General as the monarch’s appointed representative), the House of Representatives and the Senate and it is given the

legislative power of the commonwealth.

The Governor-General has the power to:

… appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit, and may, also from time to time, by Proclamation or otherwise, prorogue the Parliament, and may in like manner dissolve the House of Representatives.

It provides that parliament must meet at least once per year: there cannot be a twelve month gap between parliamentary sessions (the 1689 requirement for ‘frequent’ meetings of parliament). Many of the provisions are the details of numbers (but also allowing for later changes by the parliament), election of the Speaker, the conduct of elections and so on but it also spells out the functions for which the commonwealth parliament is responsible and these provide the basis on which the High Court decides whether or not commonwealth legislation is valid.

In our modern economy the commonwealth’s powers have actually increased as a number of its powers are only operative when an issue goes beyond a single state’s borders: for example, banking, insurance, arbitration of industrial disputes, commerce. Now it is more often normal for those matters to operate beyond the bounds of any single state. The commonwealth can also take on or share additional powers with the agreement of the states and that has happened in regard to, for example, income tax and universities.

Our constitution sets in law that proposed laws for appropriations or taxes

cannot originate in the Senate — matching Henry IV’s grant of such power to the Commons in 1407. We do not have a Standing Order 66 limiting money matters to motions of a minister (at least not that I could find) but we do have Section 56 of the constitution that states that votes on appropriation Bills can only be taken after the purpose of the appropriation has been recommended in a message from the Governor-General.

Importantly the constitution establishes the right of the people to elect the members of parliament: the phrase ‘directly chosen by the people’ is used in regard to both the Senate and House of Representatives. That gave rise to the High Court’s decision that there is an implied right of freedom of speech, at least regarding political communication, because it follows that people should make an informed vote and therefore require free expression of political ideas to inform them.

Given the people’s right to elect the members of parliament, the constitution sets out that Senators will be elected by each state voting as one electorate ‘until the Parliament otherwise provides’. So although the parliament has the power to change how the Senate is elected (perhaps by creating ‘divisions’ within a state), we have kept that system of a single electorate and used proportional representation since 1948. The States do retain many powers relating to the Senate including the right to issue the writs for Senate elections and to select replacements in the event of vacancies.

While the constitution nominated the number of members for each state in the House of Representatives for the first election, it provided that in future the number of members in each state would be determined by:

- dividing the total population of the six states of the commonwealth by twice the number of Senators to obtain a ‘quota’ (the territories are not included in the population count, nor are their Senators included, as they did not exist at the time) and note that this is the ‘total population’ not just the number of voters

- then dividing the population of each state by the ‘quota’ and rounding to the nearest whole number — provided that none of the original states can have fewer than five members.

That is still the way the Australian Electoral Commission

calculates the number of seats to which each state is entitled and is now also applied to the NT and ACT although they are not counted in determining the ‘quota’. The proviso regarding the original states allows Tasmania to retain five seats even though by the ‘quota’ method it is currently entitled to three.

It was allowed that the members of the House of Representatives could also be elected in that first election by the state voting as one electorate if a state had not yet created ‘divisions’: the commonwealth parliament, however, had the power to determine how this would be done in the future. We basically adopted a modern system of ‘boroughs’, or ‘divisions’, or what we commonly call ‘electorates’ (the Australian Electoral Commission still calls them ‘divisions’). Although only the number of seats is specified by the constitution, the

Electoral Act requires that within each State each electorate should contain approximately the same number of

voters.

The most interesting part of the constitution concerns the executive: it is clearly a constitutional monarchy and legally sets that out, relying on the the conventions inherited from England to underpin it.

The Executive power of the Commonwealth is vested in the Queen and is exercisable by the Governor-General as the Queen’s representative, and extends to the execution and maintenance of this Constitution, and the laws of the Commonwealth.

There it is — full stop! The monarch, through his or her representative,

is the executive.

Now the finer detail of how that works.

There shall be a Federal Executive Council to advise the Governor-General in the government of the Commonwealth and the members of the Council shall be chosen and summoned by the Governor-General and sworn as Executive Councillors, and shall hold office during his pleasure.

That follows the ancient structure of a monarch and a group of advisers and is like an Australian version of the Privy Council: legally, there appears nothing to stop the Governor-General acting on the advice of such a council irrespective of the parliament. It is mainly the conventions (or England’s unwritten constitutional rules) that give it a modern appearance.

Then come ministers:

The Governor-General may appoint officers to administer such departments of State of the Commonwealth as the Governor-General in Council may establish.

(Although the word ‘officers’ is used, it appears under the heading ‘Ministers’ and, just so there is no confusion, I point out that there is a separate section on the appointment of civil servants to those departments of State.)

And there is a provision that

ministers must be members of the parliament which, unlike the UK, actually makes that former convention law.

There is no mention of a cabinet or a prime minister, nor is it law that the Federal Executive Council must be made up of ministers, let alone members of parliament. That is where Westminster conventions come in and the history that gave rise to them. In Australia the Federal Executive Council actually comprises all ministers past and present — that allows former ministers to retain the title ‘The Honourable’ as that title relates not to their role as a minister but as a member of the Federal Executive Council. It appears that no one has ever been removed from the Federal Executive Council, although the Governor-General has that power. As in England since the 1700s, however, it is the current cabinet, as a ‘committee’ of the Federal Executive Council, that exercises the role as advisers to the Governor-General.

What helps make the system work is the provision that:

The provisions of this Constitution referring to the Governor-General in Council shall be construed as referring to the Governor-General acting with the advice of the Federal Executive Council. [emphasis added]

That effectively prevents the Governor-General acting alone except for certain residual powers left over from the days of the governors of the colonies. Apparently there was discussion during the framing of the constitution about codifying those ‘reserve’ powers but it was decided that it was too difficult and best left flexible (and the British government had also advised against it which meant the constitution may not have passed the British parliament if we had persisted).

When the constitution and the Westminster conventions are put together, the Governor-General is, in most matters, effectively tied to following the advice of ‘the government of the day’ which brings us back to ‘cabinet government’ and

places effective executive power with the cabinet. But that is not the law, only convention. It would theoretically be possible, and seemingly legal, to appoint non-parliamentarians to the Federal Executive Council but that would require that they are also able to have the executive decisions

legislated by parliament — hence we are back to the need, first identified over 300 years ago, to have members of parliament, particularly those who can command a majority in (or have the confidence of) the parliament, as advisers (members of the council). For even longer, those advisers have been ministers responsible for the different aspects of government — the departments of State which under our constitution must be created by the Governor-General with the advice of the Federal Executive Council. Our constitution states that all ministers must be members of parliament and all those members of parliament must be ‘directly chosen by the people’. In those ways the system links the council, cabinet, ministers, the elected members and the voters by a combination of law and convention:

- the Governor-General acts with the advice of the Federal Executive Council — law

- the role of the Federal Executive Council is fulfilled by the cabinet — convention

- the cabinet comprises ministers — convention

- ministers are members of parliament — law

- members of parliament are directly chosen by the people — law

By the time Australia federated, we already had parties in place but not as we know them today. As we were just taking the first step to become a nation, the parties generally were organised within each state. At the first federal election in 1901 the two major parties were the ‘free-traders’ (officially the Australian Free Trade and Liberal Association) centred in New South Wales and the Protectionist Party centred in Victoria. Although not nationally organised, most candidates across the country did declare themselves as either free-traders or protectionists. And each state, other than Tasmania, had its own labour party. At that first election, 31 protectionists were elected to the House of Representatives, 28 free traders, 14 state labour members, and two independents who later joined the labour party (King O’Malley had been elected in Tasmania as ‘independent labour’ and the other was, in any case, a former member of state labour). A national parliamentary labour party (Labour — it became Labor in 1912) was formed when those elected state labour members first met at the parliament in Melbourne and Chris Watson was elected as the first national leader. The first government, headed by Barton, was a protectionist minority government with Labour support and had to meet a number of Labour demands.

At the next election in 1903, 26 protectionists, 25 free traders and 23 Labour members were elected, which led in 1904 to Labour splitting from the Deakin government and forming the first Labour government. It was short-lived (only four months) but helped lead to the realignment of Australian politics.

Tariffs were the major source of revenue for the early commonwealth governments and even some free-traders supported a limited range of tariffs for that reason. With Labour and protectionists supporting tariffs, by 1906 the free-traders had basically lost the argument and renamed themselves The Anti-socialist Party.

In 1909, Andrew Fisher was leading a Labour government and pursuing

a labour program of legislation:

Far more provocative was the Labor proposal for a land tax to break up large estates and promote closer settlement, and the proposal to strengthen the Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904. Perhaps the most contentious Labor project was the planned ‘new protection’ referendum to amend the Constitution and give the Commonwealth government the power to tie labour protection to industry protection.

This Labor program was precisely the bonding agent needed to bring all three non-Labor groups in federal parliament — Deakin’s Liberals [formerly protectionists], the Anti–Socialists … and John Forrest’s ‘Corner’ [a WA party] — into coalition.

Those groups merged to form the “Commonwealth Liberal Party’. And that is how it has been for most of the time since, a basic division between Labor and anti-Labor forces.

Rather than finishing this with the traditional

TPS ‘What do you think?’, it seems more appropriate, as an information piece, to ask:

Do you have any questions?

We hope you enjoyed Ken’s two-part explanation of the complicated 800 year story that led to the parliamentary system we have (he does apologise for it being so long but suggests that it amounts to only about six words per year!). As Ken invited, we also urge you to express your thoughts on our system and ask questions. Based on the research he undertook, Ken will do his best to answer your questions.

Next week we resume normal transmission with a piece to get us in the mood for the resumption of parliament: ‘Winter winds, wind farms and hot air’ by 2353.

Current rating: 0.4 / 5 | Rated 13 times