-

16/11/2016

-

2353NM

-

supply and demand

Housing affordability is perceived to be an issue in Australia. In some areas of Australia, the median price of a house is in excess of $1million and there is some justification in the common questions around how on earth can a young couple ever be able to afford a house in that market. There are a number of answers to the question and there are also a number of inequities that are assisting to take house prices in ‘desirable’ areas out the reach of those who are not on a well above average income.

Most would attest that the choosing of a home either to rent or buy is not the stress-free experience that is portrayed in advertising for various real estate agents. For a variety of reasons, I have recently sold and purchased a home, which apart from the angst over someone paying me as much as possible and my payment of as little as possible, gave me a few insights into the current state of play in the residential real estate market.

In short, it is easy to believe that the real estate market is loaded against those who are younger, not earning that much (when compared to those who have been in the workforce for a while), with little or no deposit to contribute to the purchase of a house to call ‘their home’.

Generally, in Australia, the suburbs closer to the CBD in each capital city receive better services. There is a better variety of shopping centres, the public transport is usually better and more frequent, healthcare and education facilities are closer and accordingly easier to get to and so on. On the downside, there is a higher chance of living in a noisier environment with closer neighbours, more traffic and congestion.

Each member of the finance industry collectively spends a lot convincing you to borrow money from them rather than the mob down the road. What they don’t tell you in the glossy advertising is that if you have less than 20% of the purchase price of your future home, you will be required to pay mortgage insurance.

Normally an insurance policy paid for by a particular person will benefit that person. Mortgage insurance doesn’t. The ‘logic’ behind mortgage insurance is to pay out the financier of the home loan should the loan default. While the lender may get all their money back, the mortgage insurer is then out of pocket and chases the borrower. The insurance premium is frequently in the tens of thousands.

While there is probably some statistical reason for the requirement for loan insurance for those with what the finance industry considers to be a low deposit, it effectively penalises those who can’t for some reason save the ‘reasonable’ deposit for the area where they would like to live. The purchaser is then forced to live further away from the CBD, in an area with less services. Sooner or later pressure is applied to all levels of government for the services to improve further out from the CBD, applying upward pressure to taxes and charges so the improvements can be funded.

According to

Realesate.com.au, the time it takes to save a deposit to purchase a ‘median priced’ house in each capital city varies according to the city, number of incomes and the earnings capability of the people involved. It could take in excess of

eight years to save the 20% deposit to avoid the mortgage insurance. Don’t forget that while you are saving for the eight years, the house prices will go up as will your income. However, with housing prices in some areas rising faster than salaries and wages, is it any wonder that people decide that the occasional $22 smashed

avo on bruschetta is more attainable? If you follow the advice in this

ABC website article, you might actually have your avo while saving for the home of your own, but it isn’t guaranteed.

A considerable number of people saving for a house are renting somewhere while they ‘save the deposit’.

Realestate.com.au listed the ‘cheapest five’ rental suburbs within 10km of the respective capital city CBD

during October. Looking at the Brisbane suburbs listed on the website, the latter three generally have much better access to services than the first two, which probably accounts for the difference in price. So while paying generally in excess of $300 a week to rent a place to live, people have to find a way to put a similar or greater amount away to eventually buy a house.

Unfortunately the area with the cheapest rentals is not necessarily one of the cheaper areas to purchase in, leading to people either having to save a higher deposit or accept a reduction in nearby services when they choose to commence the process of buying a house.

That’s when you meet the real estate agents and the house sellers (better known as vendors). Real estate agents generally are paid on a commission basis. The seller of the property generally pays a certain percentage of the eventual purchase price to the real estate agent for the work they have put into introducing the purchaser to the property. In the past few months I have met some really nice people working as real estate agents and some that would sell their mother for five cents.

Observation would tell you that most real estate agents work out of offices with a number of other agents. As a result, you would think that if a customer of real estate agent ‘A’ is looking for a particular type of house that real estate agent ‘B’, who works in the same office had just been employed to sell, ‘A’ and ‘B’ would talk to ensure that the property owner and potential purchaser would be given an opportunity to sign a contract of sale. You might think it, but there is no guarantee of it happening as the usual arrangement would be that real estate agent ‘B’ would have to share his commission and may not want to do so.

Vendors have expectations of the price they want for their properties. These expectations could be related to what is needed to ‘move on’, what they have seen the house next door sell for, what the estate agent tells the seller the place is worth or some other completely rational (to the vendor anyway) process. It stands to reason that vendors want the highest price they can get as do the real estate agents (to maximise their commission payment). The next group don’t.

Purchasers are the people who drive around the area they intend to live in, traditionally on a Saturday morning, looking at houses that they can ‘live with’. Purchasers are usually limited by some financial impost, either the deposit they have available, ability to make the repayments on a loan or the need to keep some money aside to pursue some other goal.

The vendors employ the real estate agents to sell their property with the expectation that the agent has the requisite skills to achieve the highest price. The agent also wants to achieve the highest price, as it maximises the commission paid. Unfortunately, the purchaser wants to find a house for the lowest price. In an economic sense, the real estate market cannot be a completely transparent market as the agent and vendor are both attempting to achieve the highest price — only limited by the purchaser’s negotiation skills or the need of other vendors with similar homes who also want to sell their house at the same time.

The purchaser who is attempting to buy their first home is also up against the investor. Peter Martin, the Economics Editor for Fairfax’s

The Age recently looked at what could be considered to be the constant battle between

owner-occupiers and investors, noting the Reserve Bank’s comment in evidence to a recent enquiry: ‘It is a truism that if an investor is buying a property, an owner-occupier is not.’

According to Martin:

What matters for a tolerable retirement (far more than superannuation) is owning the home in which you live. If you do, the age pension is enough to get by on. If you don't, you have to pay rent. Morrison's own figures show we are condemning more and more Australians to retirements burdened by rent.

Liberal MP John Alexander started an enquiry into housing prices back in the day when Abbott was the prime minister and Hockey was the treasurer. The enquiry was allowed to lapse after the recent election but Alexander was moved on about a year prior to that.

Hockey’s Treasury Department made a submission to Alexander’s enquiry. In the words of Peter Martin:

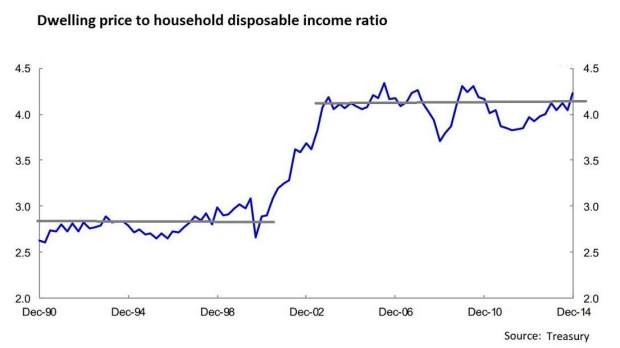

Graph 13 in its submission shows that up until the end of the 1990s the median dwelling price stayed in a tight band of 2.5 to 3 times household after-tax income. Then in the space of three years it shot up to near four times after-tax income and has stayed there ever since.

What happened at the end of the 1990s? In September 1999, the government halved the headline rate of capital gains tax, making negative gearing suddenly an essential tax strategy. Whereas before, renting out a house at a loss for tax purposes had been mainly an exercise in delaying tax because the eventual profit made selling the property would be taxed at close to the seller's marginal rate, afterwards, with the profit taxed at only half the marginal rate, it became an exercise in cutting tax.

So those with a desire to cut their tax took the opportunity given to them on a plate by the Howard government and negatively geared a house. Howard used to claim that rising housing prices were a sign of a good economy. The problem is that the investors (and more recently those from overseas) are in a position to squeeze owner-occupiers out of the market by bidding up house prices. The vendors and agents are happy — they are getting more money at the time of sale; the investors are effectively and legally writing off tax they would otherwise have to pay; and those who are trying to get their foot in the door are priced out of the market. After all the areas that are attractive to owner-occupiers because of features such as services or the natural surroundings are also attractive to investors, as the same attractions are also valuable to renters.

Take it from me, buying and selling houses is not the easy process that is commonly suggested in the advertising from real estate agencies and financial institutions. It is apparently worse for someone who is buying a house for the first time — as discussed by Erin Munro on the

Domain website.

Current treasurer Scott Morrison made a speech to the Urban Development Institute recently where he called on state governments to reduce artificial constraints on

housing supply. While there are probably some constraints that do require attention, maybe Morrison should take care of his own backyard first. The ALP had a policy at the last federal election to reduce the benefits of negative gearing and capital gains tax for those who invest in residential housing — maybe they were on to something.

Peter Martin suggests:

Reinstating capital gains tax and imposing a land tax would help, as would building more houses. But there is something in our psychology that's doing it as well. We seem to want to push up the prices we complain about. Adding "supply" might do no more than give us something else to bid up.

Until some rationality is restored, if someone in your family wants to buy a first house, best of luck.

Current rating: 0.4 / 5 | Rated 12 times