In my pieces I often refer to neo-liberalism. As explained in my pieces last year, ‘

Whose freedom?’ and ‘

Whose responsibility?’, the neo-liberal idea of freedom is based on the rational self-interested individual and it also adopts the approach of ‘negative’ freedom (following Isaiah Berlin as explained in ‘Whose freedom?’): that is freedom from interference or coercion. It is the modern version of the old libertarian.

It is also based on the principle of property rights: that I am the owner of myself and of everything I create and I should, therefore, be free to determine what I do with that property.

Their approach, however, has a problem. Its logical and pure outcome is anarchy. That comes about because if we are each rational individuals able to make rational decisions in our own self-interest, without the need for external influences to direct us towards beneficial decisions, then there is no need for government or rules — that is total freedom from interference. Can you imagine such a world? Neither can any but the most extreme libertarians and neo-liberals. But they do like the idea of ‘small government’, minimal tax and minimal regulation.

Political philosophers have often begun with what they term the ‘state of nature’, a construct meant to envisage human society before political structures.

Hobbes and

Locke ended up with opposing views on that ‘state’: Hobbes thinking it was one of constant conflict and Locke seeing it as harmonious, although with the potential to lead to conflict. What they did agree was that there was a ‘social contract’ whereby people gave up some of their freedom for the protection of the state, or government. Hobbes saw that leading to the need for strong government and consistent enforcement of the rule of law to restrain the inherent conflict, while Locke saw the government as existing only because the people granted it the capacity to exist — the state’s primary role was to protect the individual’s property (including the person). Locke is considered the ‘father’ of liberalism.

For neo-liberals, however, the ‘social contract’ raises a philosophical problem because it is seen as binding the property rights of future generations. For them, if a ‘social contract’ exists to give rise to government, and a monopolistic power of protection and coercion, it should be renegotiated by each generation. Otherwise they are back to their state of pure anarchy. So they needed another way to explain how government arose and it was provided by a philosopher in the 1970s — Robert Nozick.

Nozick posited that ‘the state’ could arise from the actions of individuals. While he saw rational individuals acting ‘morally’ in the state of nature (as Locke did), there could arise occasions where some did not act ‘morally’ forcing those under attack to join ‘mutual protection agencies’:

These agencies sell security packages like a free market economic good that individuals in a state of nature would surely buy for self and property protection.

So the individuals become clients of the agency when they purchase its protection. The steps involved in those mutual protection agencies developing into a state are:

- A mutual protection agency becomes a dominant or pre-eminent protection agency in its territory.

- It becomes what Nozick calls an ‘ultra-minimal state’ when it gains a monopoly on force in the region, even though protection is still purchased as an economic good.

- The minimal state emerges when the first two conditions are met but the agency also extends protection to non-clients within its territory — which then comes at a cost to its clients.

For neo-liberals, this approach follows market principles and is based on the rational self-interested individual voluntarily purchasing protection from ‘the state’. The state then also has a role in stopping people enforcing their own protection against other individuals as it has the monopoly on coercive force.

It was not just the explanation of the rise of the state but the implications it gave rise to that attracted neo-liberals.

Nozick considered that the state’s single proper duty is the protection of persons and property and that it requires taxation

only for that purpose. Taking tax for redistributive purposes is on a par with forced labour:

Seizing the results from someone’s labor is equivalent to seizing hours from him … If people force you to do certain work, or unrewarded work, for a certain period of time, they decide what you are to do and what purposes your work is to serve apart from your decisions. This process whereby they take this decision from you makes them a part-owner of you; it gives them a property right in you.

So from the neo-liberal perspective, taxation, other than to provide for protection of the person and property, gives the state a property right over us and therefore is an intrusion on individual rights — someone else is deciding what to do with the results of an individual’s labour. (

Hockey’s claim that we work more than a month just to pay for welfare can clearly be seen as based on this argument and seemed to be driven by the false assumption that everybody else, not just he, believed it.)

Nozick also saw no philosophic problem with inequality. As each individual owns the products of their own endeavours and talents, it is possible for an individual to acquire property rights (as long as they are not gained by theft, force or fraud) over a disproportionate amount of the world: once private property has been appropriated in that way, it is ‘morally’ necessary for a free market to exist so as to allow further exchange of the property. And the individual then has complete control as to how that property is passed on. So it is logically okay for someone to inherit a fortune having contributed nothing to gain that wealth: reward for effort or just desert do not come into it for Nozick — it is only property rights and market mechanisms that count. ‘Reward for effort’ has remained, however, in the neo-liberal lexicon to justify the extreme wealth that some, like Trump, have obtained and to allow them to argue that the less successful have simply not put in enough effort.

There is also no such thing as the ‘common good’ in this approach, only individuals:

While it is true that some individuals might make sacrifices of some of their interests in order to gain benefits for some other of their interests, society can never be justified in sacrificing the interests of some individuals for the sake of others. [emphasis added]

In summary:

The state then can be seen as an institution that serves to protect private property rights and the transactions that follow from them regardless of our thoughts of some people deserving more or less than they have.

You can see why neo-liberals and capitalists generally were happy to have such a philosophic basis for their actions (even though Nozick later retreated from some aspects of it).

That whole approach adopted by the neo-liberals, and their economists, ignores the evidence that humankind is a social animal (see ‘Whose responsibility?’ linked at the start of this article). I won’t reiterate that aspect but want to consider the evolutionary psychology theory around ‘coalitions’ — which are also part of our social being.

Basically it says humans have an evolved tendency to form coalitions, a

stronger tendency in men than women according to the researchers. It also leads us to recognise categories of ‘us’ and ‘them’. For prehistoric humankind, this may have been an essential element for survival: an ability to recognise those whom one could trust and rely on from those who may pose a threat or, at the least, not provide support or assistance when needed. It also included a major element of reciprocity: I will support others in the coalition because I know they will in turn support me.

Modern experiments have suggested that the need to form coalitions can

over-rule ‘race’ as a categorisation. That has led some to suggest that ‘race’ is merely a form of coalition that can be over-ruled by circumstances. (Categories based on age and gender are not affected in the same way.)

The reciprocal nature of coalitions has been

tested against ‘game theory’. In game theory it is said there are three basic approaches:

co-operate with opponents to maximise group benefits (but at the risk of being suckered);

free-ride (try to sucker co-operators); or

reciprocate (co-operate only with those who show signs of co-operation but not with free riders). Economists talk about an equilibrium being achieved in which individuals adjust their behaviour in order to maximise their own gains; but evolutionary psychology says that these approaches will not be equally represented in society, that there are ‘evolutionary stable strategies’ hard-wired into the human brain (which can be over-ridden but remain a default position). In recent experiments, the evolutionary approach has come out on top. In a series of four-player games 63% were found to be reciprocators, 20% free-riders and 13% co-operators but, more importantly, the researchers were then able to predict the result of further games because most individuals did not change their strategies (or did not adjust their strategies to maximise personal gain as the neo-liberal economists predict) — the missing 4% in those numbers could not be readily fitted to the three categories which, I assume, means they did change strategies and that may also suggest that only 4% of the population utilise the neo-liberal position. If reciprocity is such a highly valued approach, then it supports the view that we are hard-wired to identify and participate in coalitions and are also hard-wired to identify ‘cheaters’ or ‘free-riders’ — which is what governments are appealing to when they refer to ‘dole bludgers’ and ‘welfare cheats’ when cutting social welfare payments.

Political parties themselves are a coalition and have a coalition of supporters. Those coalitions are quite strong: Obama can be elected as a Democrat despite his race. That is one reason the old adage of ‘never discuss politics or religion’ has some validity. It is to enter into a discussion in which coalitions are already strongly formed and expressing your opinion may only identify you as an outsider.

We must also remember that coalitions can be flexible. People can come and go, or join a different coalition. Coalitions may also disappear completely if the reason that gave rise to them no longer exists or its leader falls and the coalition fragments.

Politics and religion, however, are now institutionalised, so they can continue irrespective of their original purpose and irrespective of movements in the coalitions associated with them. In evolutionary terms we looked to physically strong, reliable and trustworthy leaders if we were to join a coalition in the first place — it may have been to raid a neighbouring village. In our institutionalised coalitions, changes of leadership do not really change the structure of the coalition but we still carry that evolutionary approach and see a change of leader as a potential threat to the coalition – á la the public reaction to Rudd being dumped. The Turnbull ascendancy has been easier. The major difference would appear to be that Abbott was already in a position where he was no longer seen as a trusted and reliable leader of a coalition, although he was attempting still to portray himself as a strong leader — one out of three wasn’t good enough!

What I find fascinating is the contradiction between the two approaches I have described. Despite a natural propensity to form coalitions and engage in reciprocity, the neo-liberals continue to tell us that we function as individuals seeking only our own advantage. From the evidence, it is based on a philosophical myth that ignores the way humans actually behave. It is a construct of an ‘economic being’ that appears to have little relationship with reality.

It leads to businessmen expressing their natural humanity by forming coalitions, locally, regionally and nationally, while at the same time fighting the very existence of workers’ coalitions (unions).

We have our current government, itself derived from coalitions (the Liberal and National parties as separate coalitions of like-minded people who have the same or similar goals — their formal ‘coalition agreement’ so as to govern is a different matter). Although arising from coalitions, in the evolutionary sense, the government insists it should treat us only as individuals and ignores the coalitions we may form.

Despite insisting on the economic individual as central to policy, Abbott commonly resorted to the ultimate coalition — nationalism — to justify his leadership: there were people out there ‘coming to get us’; we had ‘Team Australia’; and you were either with us or against us and, if against us, may lose your citizenship. A blatant appeal to our evolutionary trait of identifying ‘us’ and ‘them’. While Turnbull may not play the nationalism card, he has

made it clear that his will be ‘a thoroughly liberal government committed to freedom, the individual and the market’, exactly the foundations of the neo-liberal approach. As this was from his oral victory speech, it is not clear whether he meant ‘liberal’ or ‘Liberal’, and I did note that different on-line media sites used those different forms of the word, but it does not change the point that, either as a Liberal or liberal, he is promising a neo-liberal approach.

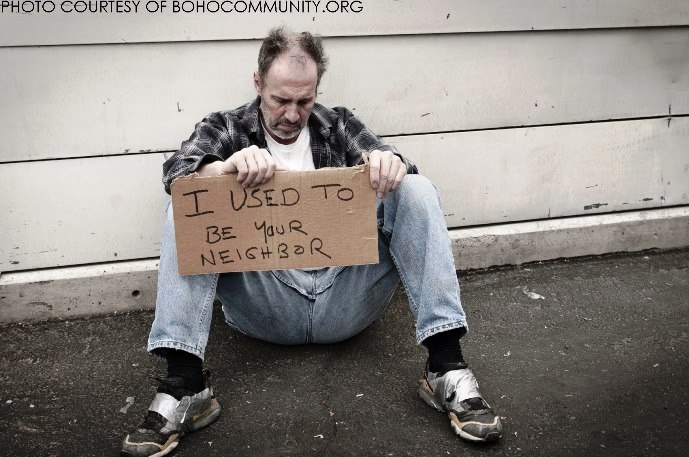

Stressing individuality supports the success of the rich businessman (like Turnbull) but leaves the poorer individual helpless (and, ironically, more dependent on government or community support). It basically matches Nozick’s view that inequality is irrelevant.

Logically, the government cannot have it both ways: we are either all individuals, in which case nationalism has no place and business coalitions should be ignored, or we are all members of various coalitions, from the nation state to local groupings, and the government should recognise those coalitions, engage with them and recognise them in policy. Instead it engages with the business coalitions but insists the rest of us are mythical individuals and Turnbull’s words in his victory speech suggest that is unlikely to change.

What do you think?

Heavy, ay? If the economic individual created by neo-liberalism is a myth, where does that leave the philosophic basis of the Liberal party? Should a Liberal party even exist? — it is, after all, a coalition. Should government policy, as Ken suggests, focus on groups, the coalitions we naturally form, rather than the individual? Would that work? Let us know what you think.

Next week 2353 looks at some of the turmoil created by Turnbull’s ascension to prime minister in ‘Pass the popcorn’.

Current rating: 0.4 / 5 | Rated 12 times