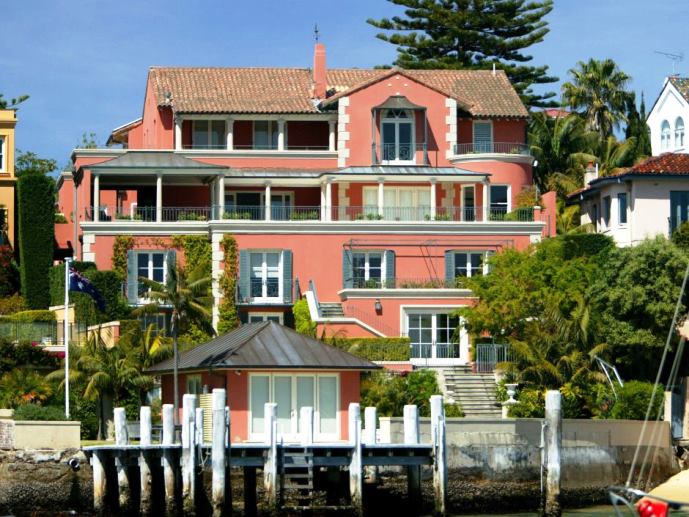

[The Turnbull residence at Point Piper, Sydney]

After Turnbull toppled Abbott in September the polls turned in favour of the Coalition; Turnbull’s ‘satisfaction’ rating was high; and he had a commanding lead over Shorten as preferred prime minister. The big question for Turnbull, the Coalition, and indeed Labor, is whether he can maintain those poll numbers all the way to an election.

In my view there are already signs that suggest he will not. That may not yet be showing in polling but unless he acts to meet public expectations those polls will slowly drift away from him.

When Turnbull first won the post as prime minister, he could not stop smiling. In his victory speech, in early interviews and press conferences, he was ceaselessly smiling. Between christmas and new year, when he announced the demotions of Brough and Briggs, he was no longer smiling. Perhaps it was no smiling matter but it was a hint that the pressure of the job is starting to tell.

Turnbull has a reputation as a ‘small l’ liberal with his views on gay marriage and climate change. He does represent an electorate where such views go over well and, especially after Abbott, the wider electorate also saw such views as a hopeful sign for the future. So far, however, Turnbull has done nothing to action such views: he has accepted the position that the gay marriage issue will be put to a plebiscite and not just a parliamentary vote; and, although signing up to the Paris agreement on climate change action, he will stick with Abbott’s ‘Direct Action’ policy (which most experts suggest will fail to deliver). It appears this is a result of deals done with the Right of the Liberal party to secure the top job or, at the least, bowing to the reality of the number of far Right members in his party. It is, however, creating disillusionment in the electorate. As most people accept the reality of politics, he will be given time to make changes but he will not be given forever. While he may wish to make changes, he is hamstrung by the deals he did and the numbers in his party who do not support his more liberal views. Unfortunately, he may not have the power within the party to over-rule those deals until he wins an election (when he can then claim leadership in his own right) but ironically he may not win an election unless he makes those changes first — a classic Catch 22!

Turnbull arrived as a breath of fresh air, saying the right things, and appearing as a very different politician to Abbott. But the announcement about Brough and Briggs (and the abandonment of the Gonski funding model for education which was announced at about the same time) was made during a period, between christmas and new year, when the attention of most people was on issues other than politics. To the cynical amongst us, which now includes a majority of people when it comes to politicians, it gave the appearance of deliberately trying to ‘bury’ the news. (The news about Brough and Briggs was effective in burying the Gonski announcement.) For someone who first appeared as ‘different’ to Abbott, that is a fail. It tends to suggest that he is merely another politician, not better nor worse, but just as willing to play political games. That is not a view that fits with how he first attempted to portray himself and the electorate will add that to the list when adjudicating on his prime ministership. On its own it may not change the electorate’s view but it is another straw on the camel’s back.

The Trade Union Royal Commission (TURC) was initiated by Abbott but its report was delivered to and released by Turnbull. He described it as a ‘

watershed moment’ for the labour movement. Making so-called union corruption an election issue, which he also promised, is a double-edged sword. Union bashing (and by association Labor and Shorten bashing) goes over well with some but unions can be effective in fighting back as they proved with WorkChoices. Turnbull is trying to frame it (following Ad Astra’s explanation of ‘framing’) as in the interest of ordinary union members but much will depend on the frame the unions use in fighting back.

The Guardian has already pointed to the number of powerful

women in the union movement and suggested:

A rise in female leadership and the diversity of social backgrounds from which they come has delivered to the union movement a face that looks far more like Australia’s than the Coalition’s own cabinet.

The public are also aware that the

ATO released information that almost 600 of Australia’s biggest companies paid no tax in 2013‒14. While there are many reasons for that, the bald facts suggest that companies can avoid tax with impunity which reflects poorly on the government.

Senator Xenophon has raised questions about the company that bought the Dick Smith electronics chain and floated the business in December 2013 making a profit of $400 million only to see the company now in voluntary administration. Echoing the TURC terms of reference, Xenophon said: ‘There are some real questions to be asked here about our level of

corporate governance …’ [emphasis added]

When all that is put together, I doubt that TURC will really have the impact that some in the Coalition believe. Many in the electorate will be asking questions about why the unions are being pursued but big business isn’t. It’s a fair question. Politicians lose their positions when caught out but just losing their position is apparently not enough for union leaders. A politician who rorts the benefits he or she is entitled to is allowed to pay the money back but a union leader faces fraud charges. Some in the electorate already recognise the inconsistency and see it continuing under Turnbull.

Turnbull also appears happy to reduce penalty rates but lower wages not only affect workers but mean lower tax revenue for government. Bosses have argued since time immemorial that lower wages allow them to employ more people but it has never happened: during the Great Depression the then Arbitration Commission reduced wages in Australia by 10% with businesses promising they would then be able to employ more people but unemployment continued to rise, from 20% to 30%. Turnbull, however, side-stepped the issue by saying it was a matter for the Fair Work Commission. That is not what people expect of their government: government representatives will most likely make representations to the Fair Work Commission when the case comes up and people expect to know whether the government will support or oppose a reduction in penalty rates. Simply pretending that it is nothing to do with him, is not what people expect of a prime minister.

When it comes to economic policy? — no change there. The Turnbull government is still attacking those lower on the pecking order and leaving business and the well-off alone to get on with the job of making money — sorry, according to Turnbull that should be getting on with creating jobs. Despite Turnbull telling us that his approach will be ‘fair’, he should be conscious of the reaction to the 2014 budget when it was commonly and widely believed that the burden of cuts fell disproportionately on the less well-off. If people perceive that is still happening, or happening again, Turnbull’s claims of fairness will be seen as meaningless and just political ‘clap trap’ — not good for a politician’s future as Abbott and Hockey discovered. Of course, the idea of an increase in the GST is still alive, although opposed by a majority of voters.

The lack of activity by the government is reflected in the real economy. In December

construction activity declined and there was also a downturn in new orders going into 2016; and a

business survey found companies had lower expectations for sales, profits and employment in 2016. Around 70% of voters consistently rate the economy as an important issue and these indicators do not bode well for the government in 2016.

The approach to TURC and economic policy suggest that Turnbull is, at heart, still a businessman and will support big business. He may have small ‘l’ liberal social views but displays neo-liberal economic views and that will become more apparent to the electorate as time passes, and will be exacerbated if he fails to implement some of his social views.

To date, Turnbull has made only one significant new policy announcement — the science and innovation policy. There are a lot of words about a ‘cultural’ shift but little on where the money comes from: it appears that some funding is still dependent on the Senate passing previous cuts proposed by Abbott and Hockey. There have been a series of lesser announcements by his ministers, some of which seem to have had little attention in the media, but which together add up to more cuts to health and welfare spending, such as changes to paid parental leave, to Medicare benefits and to the eligibility of former public servants (both state and federal) for a part-pension. While not all of these measures have attracted wide attention, the people affected are certainly well aware of them and as the number of these groups is added to, that is a growing number of voters who are becoming more disillusioned, more convinced that the Abbott approach is continuing.

The Turnbull government is still pursuing the Abbott government policy of a transfer of powers to the states. Morrison has floated the idea that the states should receive a guaranteed share of income tax. The underlying idea is that the states become solely responsible for schools and hospitals and the commonwealth covers Medicare, the PBS and universities. Given that education and health are issues which the electorate sees Labor as better able to manage, the cynic in me suggests that this is also a political strategy to take away one of Labor’s strengths at the federal level. I do not expect everyone to see this, but people will see the commonwealth withdrawing from hospital and school funding. For many years now, commonwealth financial support has been central to health and education and it will be difficult to change that public perception. That leaves some room for Labor to continue pursuing commonwealth involvement in health and education because, at least for now, that is what the electorate expects.

Decisiveness is lacking or, at least, there is no sign of it yet. It is all well and good to make promises about consultation and proper consideration of issues but people often expect their leaders to be decisive, even with less popular decisions. Four months into his prime ministership and Turnbull has not made any major decisions — he has simply continued the Abbott policies. People expected there would be changes in the policy approach but are not seeing that. Turnbull may have provided a fresh approach in his words and demeanour but not in policy and that will soon wear thin with the electorate.

Some of these issues suggest there may be a temptation to go to an early election before the gloss of the Turnbull leadership wears off and more expectations are left unmet. At an election, however, he would be required to put policies before the electorate and if they remain the Abbott policies, the electorate will not be well pleased. Also if he goes before he has even presented his first budget, it will suggest signs of panic. The budget is often seen as a key indicator of the direction of a prime ministership and to go to an election without presenting one is not a good look. Turnbull, however, is trying to frame an opportunity to go early by using the TURC recommendations and associated legislation as a potential trigger for a double dissolution. Most commentators doubt that a double dissolution will be called because of the likelihood that it would give rise to an increase in minor parties in the Senate (owing to the smaller quota required to win a seat). There may not be a double dissolution but Turnbull may still be tempted to go early — how early is the question, as that also depends on a number of legal requirements regarding the timing of House and Senate elections. Legally he could hold just a House election but it would be electorally unpopular to again separate House and Senate elections. So his options for an early election appear limited, giving the electorate more time to see his true colours.

On 29 January, however, he did indicate that an election would not be called until August, September or October, thus acknowledging the difficulties of going early, but only a few days later, on the first sitting day of parliament, he said a double dissolution was still a ‘live option’ — although that may have been intended to pressure current cross-bench senators to support his legislation rather than a genuine intention. The fact that he can express those contradictory positions within a few days does not present the image of a decisive prime minister.

Basically, Turnbull created a persona before he became prime minister that is not being matched by his actions as prime minister and the electorate will grow increasingly disillusioned with this. So I think there is reason for optimism that the Coalition can be defeated in the election this year. The big question is whether Labor will be able to take advantage of this — but I will save those speculations for another time.

What do you think?

Is Ken’s optimism justified? Will people see through Turnbull’s glossy veneer before the election or will awakening come too late? Can Labor be effective in highlighting Turnbull’s ineffectiveness?

We hope you noticed that this piece was posted on Sunday morning rather than our previous regular time of Sunday evening. This will become our new standard posting time (9.00am on a Sunday) allowing you time to catch up after breakfast or brunch (depending on your time of rising).

Next week, at 9.00am on Sunday, 2353NM discusses a link between guns and electric cars in ‘Americans aren’t the only ones with blinkers’.

Current rating: 0.4 / 5 | Rated 14 times