-

21/09/2016

-

Ken Wolff

-

Job Guarantee

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a macroeconomic theory for the current age in which governments have abandoned the gold standard and also floated their currencies. It is ‘macroeconomic’ and ‘monetary’ because many of its conclusions relate to the money supply in an economy. Does it offer scope for a new economic approach recognising people? Can it better assist responses to robotics and computerisation than current economic approaches?

Historically, gold was important because coins were minted from it (and silver). Even when coins were no longer minted in gold, the currency issued by governments was convertible to gold and governments needed to hold sufficient gold reserves to satisfy a potential demand from all holders of their currency — that was the gold standard. In that situation governments could not spend without first taking money from the economy (taxation) because the money supply was limited to match the quantity of gold. Following WW2, fixed exchange rates also meant that governments, through their central banks, had to defend the rate they had fixed by buying or selling their own currency in international money markets: that also affected the money supply in their home economy and also placed limitations on government spending. Floating currencies now allow central banks and governments to target domestic economic policy goals knowing that the floating exchange rate will resolve the currency imbalances arising from trade deficits or surpluses.

MMT points out that much economic thinking since the 1980s operates as though the gold standard is still in place — namely, that governments can only fund their spending by taxation and therefore deficits are bad — but some MMT proponents and supporters argue that this has ideological (neoliberal) rather than genuine economic underpinnings.

Since the abandonment of the gold standard, most countries, including Australia, now have a

fiat currency — that is, it is created by government fiat (decree) — and it has no intrinsic value. My $50 note is not matched by $50 worth of gold any longer, nor is my plastic note worth $50 itself (in 2012 Australia’s polymer notes cost 34c each on average to produce irrespective of their face value). My note has value only because the government decrees it has and the government is the monopoly provider of currency: therefore it is the currency I need to participate in the economy and to pay taxes.

MMT places this new reality at the centre of its approach. A sovereign government issuing its own currency can never run out of money, never go bankrupt or default on its ‘debt’. That in a sense was Greece’s problem: as part of the Eurozone it was no longer an issuer of its own currency. In that circumstance, as for the states within a sovereign nation, the oft-used analogy of a household budget still applies but it does not apply to the sovereign issuer of a currency.

The ‘sovereign issuer of currency’ argument leads to probably the most well-known and sometimes controversial aspect of MMT, that a government can always ‘create’ money. The critics argue such printing of money — although these days it actually requires only a few keystrokes on a computer to create deposits in the private banking system — will lead to hyperinflation as in Zimbabwe or the Weimar Republic in post-WW1 Germany. MMT accepts that inflation is one factor that imposes a limit on government spending but that limit is not reached until

all the ‘real’ resources of the economy are fully utilised — all human resources (full employment) using all available physical resources. If a government continues to spend after that, then dangerous inflation may result but, prior to that point, MMT argues that government spending to assist utilisation of available resources will not lead to uncontrolled inflation. For MMT, the issue is not just money but the real human and physical resources that are available to the economy and

not currently being used:

If there are slack resources available to purchase then a fiscal stimulus has the capacity to ensure they are fully employed.

As a means to help control inflation, current mainstream economic thinking accepts the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (more commonly known by its acronym, NAIRU). The Australian Treasury uses NAIRU in its modelling as the basic foundation of longer-term stable inflation — currently the NAIRU in Australia is 5% unemployment. Before NAIRU, full employment was taken to mean there would be about 2% unemployment, allowing for people moving between jobs or unemployed short term for various reasons. In practice, NAIRU provides a ‘buffer stock’ of unemployed which basically means that having those extra unemployed, above the previously accepted 2%, provides downward pressure on wages growth because the unemployed are more willing to accept lower wages simply to have a job. The argument goes that if unemployment falls below the NAIRU level the competition for workers will mean employers accept demands for higher wages thus leading to higher inflation. (Despite the whole capitalist free market system being based on competition, whenever workers appear to have a competitive advantage it is decried as a threat to the economy!)

MMT rejects the NAIRU and instead proposes a Job Guarantee for the ‘unemployed’, sometimes referred to as ‘transitional employment’ which probably describes it better. As opposed to the NAIRU ‘buffer stock of unemployed’, MMT offers a ‘buffer stock of employed’ but this is done at a ‘fixed price’ — in Australia this would be the minimum wage, inclusive of standard employment conditions. It means the government supports employment until such time as a person obtains higher paying mainstream work and it will be in productive work

using under-utilised resources:

What matters … is whether there are enough real resources available to produce goods and services that are equal in value to the government’s job-guarantee spending. If these resources are available — if they are not already being used to produce something else — then the increased demand that results from the payment of job-guarantee wages will not be inflationary, regardless of what they go to produce.

On broader monetary issues, MMT says that there can only be saving in the private sector, inclusive of banks, businesses and households, if the government spends more than it collects in taxes: that is, only when the government adds money into the economy can there be private sector saving as well as investment.

A good, simplified explanation of this was provided by

John Carney at CNBC in 2012:

The MMT people aren’t actually referring to you and I saving. They aren’t even talking about the entire household sector saving financial assets. They are talking about the entire private sector spending less money than it earns.

You can easily see why this would be impossible without the government spending more than it collects. Every dollar someone is paid is a dollar someone else has spent. If we all — every single person and company — spend less than we are paid, very quickly we will find we have to be paid less. The aggregate effect of savings is to reduce the total amount people are being paid for things.

So this is what MMT people are talking about when they refer to a “private sector desire to net save.” They mean that if you add up all the earning, spending and savings of every person and company in the economy outside of the government, sometimes you find that the private sector is trying — nearly impossibly — to earn more than it spends.

The only thing that can make private-sector net savings possible is government spending. If the government spends more than it takes in taxes, the private sector can earn more than it spends. Remember, if everyone pays less than they earn, some outsider must be paying more than he earns.

The MMT equation for this is:

(G – T) = (S – I)

Or in words, government spending (G) minus taxes (T) equals private saving (S) minus gross private investment (I). This is so because in macroeconomic terms the two represent the entire amount of money in the economy. And the other key of this equation is that it shows that money does not come into being in the private sector unless the government has first spent it (over many years now).

MMT points out that when governments run surpluses it leads to an increase in private sector debt because, in that circumstance, if the private sector wishes to save

and invest, it has to borrow from the existing pool of money (and the government surpluses are actually reducing the money supply). This is explained by the concept that transactions between banks, businesses and households are ‘horizontal’ transactions and cannot change the amount of money in the economy (liquidity). Only a ‘vertical’ transaction between the government and the private sector can change liquidity (MMT includes both the treasury and central bank when it talks of ‘government’).

In the USA, on all occasions when the government has run surpluses, and reduced debt for a few years, it has been followed by recessions or depressions. Arising from the indebtedness forced on the private sector by the government surpluses, there comes a point when the private sector reduces spending because it cannot afford to take on more debt, thus creating an economic slow-down. In such circumstances, only government spending can relieve the situation. (It is also of interest that since 1776 the US government has been in debt in every year except for the years 1835 to 1837.)

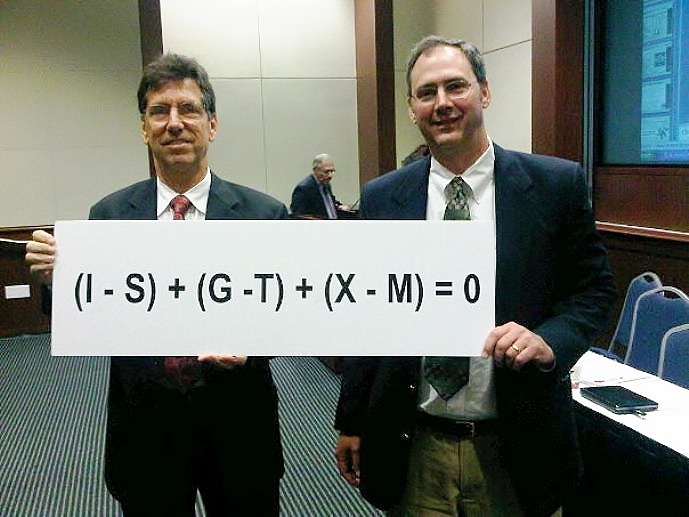

In a globalised world, however, national economies do not operate in isolation so one more aspect needs to be added to the equation: exports (X) and imports (M).

(G – T) = (S – I) ? (X – M) or

(G – T) + (X – M) = (S – I)

If a country has a trade surplus that adds to private savings. Many countries, however, as Australia, operate a trade deficit which means that private sector saving is reduced and more reliant on government spending. And at a global level the nett outcome of all countries’ trade must sum to zero, so it is impossible for every country to run a trade surplus — a surplus in one country necessarily requires a deficit in other countries. So a trade deficit or surplus is not bad in itself but does affect private sector saving and creates more need for government to adjust its spending appropriately.

Although even MMT still talks about deficits and surpluses, my reading is that those words are less relevant in MMT. If a government can create money it can never really be in deficit (except perhaps in a point-in-time accounting sense). Even claiming that the deficit represents spending more than collected as taxes is not relevant. MMT says that the government does not need taxes in order to spend — it can always create whatever money it needs. The real purpose of taxes is to take money from the economy or, in economic terms, to reduce liquidity, meaning there is less money to spend and thereby total demand across the economy is also reduced. What taxes can achieve is to create ‘space’ for government spending. If an economy is already running at capacity and the government continues to spend, that is increases liquidity and demand without first making space for that spending, then high levels of inflation may result because there is more money in the economy to buy the same amount of goods and services, meaning people competing for those goods and services are willing and able to pay higher prices to obtain them. So taxes can be important in allowing government spending without dangerous inflation but are not necessary in themselves for that spending.

Similarly MMT argues that the sale of government bonds is not necessary to fund government ‘debt’. So-called ‘debt’ can actually be met at any time because the government can ‘create’ the money to do so. But as always the limiting factor is controlling demand in relation to the capacity of the economy so as not to allow dangerous levels of inflation.

MMT’s explanation is that the sale of government bonds is primarily a means of controlling interest rates: this relates to the overnight commercial bank reserves placed with the central bank but I won’t attempt to explain how that works. (This

interview with Bill Mitchell for the

Harvard International Review provides an explanation and also a good summary of MMT.) A secondary reason is that banks, financial markets and the private sector generally, desire government bonds as a safe haven to park money. Here in Australia, that became obvious during the Howard/Costello years when the government paid down its debt and saw little need to make new bond issues but the private sector complained and the government had to issue more ‘debt’ even though it had no debt: that fact alone gives credence to the MMT argument.

Although the approach is called Modern

Monetary Theory, it places more emphasis on

fiscal policy. Bill Mitchell writing on the current economic problems said, ‘until we stop relying on monetary policy and restore fiscal policy to the top of the macroeconomic policy hierarchy, nothing much is going to change’. Mitchell argues that governments have been

using the wrong approach to overcome the current economic stagnation affecting many countries:

It is not that they have run out of ammunition. They have been using the wrong ‘ammunition’. For example, trying to drive growth with low or negative interest rates failed to work because the lack of bank lending had nothing to do with the ‘cost’ of loans.

It had all to do with the dearth of borrowers. Households, carrying record levels of debt and facing the daily prospect of losing their jobs, were not going to [start] suddenly bingeing on credit again.

Business firms, facing slack sales and a very uncertain future, could satisfy all the current (low) levels of aggregate spending in their economies with the existing capital stock they had in place and therefore had no reason to risk adding to that capital stock.

In the MMT model, the remedy to many economic problems is

fiscal stimulus not austerity which only exacerbates the problems. And as a sovereign issuer of currency the government

always has the capacity to provide such a stimulus when there are under-utilised resources in the economy.

Using fiscal policy, and the knowledge that governments can spend as much as they wish, limited only by available real economic resources and inflationary impacts, MMT suggests that the real issues are social policy issues. The debate should not be about ‘debt and deficit’ but what we as a society wish to achieve, wish to become, and, within the limits mentioned, governments do have the capacity to meet those goals. For me that is an important outcome from MMT, not just that it offers a new economic approach but that it offers scope for a new policy and political approach. To that extent, it does allow

space for people by creating an economic approach that recognises social policy goals are of critical importance and the ability to achieve them is not so limited or proscribed as it is by existing neoliberal economic theory. For that reason alone MMT deserves more attention.

Next week, in the last of this four-part series, I will consider whether governments are ready for the coming economic and social changes.

Current rating: 0.3 / 5 | Rated 16 times