-

6/11/2016

-

2353NM

-

Gillian Triggs

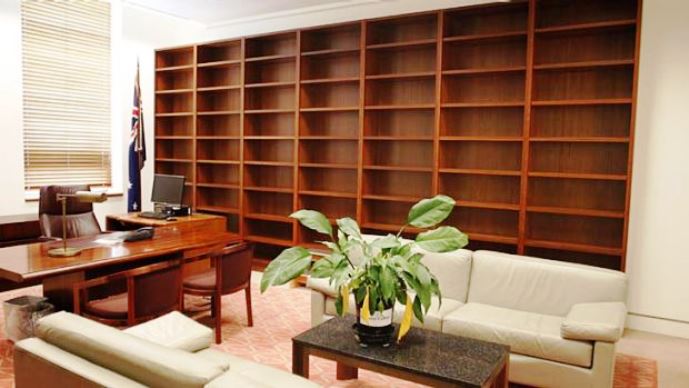

[The bookcases that were too big to move]

A lot of employers place significant levels of trust in their employees. Retailers trust their employees to charge the customers the correct amount for the products they sell and put the money into the register; airlines trust that their employees are fit and mentally capable of servicing or flying the plane they are assigned to fly; bus and truck operators trust that their drivers will drive the vehicle along the assigned route; while health care workers are trusted to look after those in their care.

At times, employees have to make decisions that may have an inimical impact on their employer’s business. The retailer’s staff usually have a mandate to deduct a percentage of the price of an item if there is some imperfection. External factors may delay the arrival time of the plane in Sydney or the 456 bus to the City. Obviously a number of 737s can’t land on one runway at the same time and if the 456 bus is caught in a traffic jam, the bus can’t push other vehicles out of the way.

This in turn affects the operation of the other services as transport operators tend not to have a spare 737 or commuter bus sitting around at every terminal ‘just in case’ something doesn’t turn up on time. This is the greater good in operation, it is better for a plane or bus to be late than for the system to fail completely because of the actions of one person who was following their employer’s requirements regardless of the outcomes.

At times there are those who try to beat the system and there are probably a set of checks to ensure that the trust is respected and the cash register takings balance the amount of stock that has left the store; the pilot for the 8.30 plane to Sydney isn’t enjoying the free drinks in the Business Class Lounge with the passengers before the flight; the heavy vehicle driver hasn’t found a nice shady spot beside a creek and decided to wet a line and so on. The number of trucks and buses in the streets of our major towns and planes that arrive and depart about the right time would demonstrate that most employees demonstrate that the trust their employers show is not misplaced.

Just about everyone who works in a shop, flies a plane or drives a heavy vehicle is paid significantly less than Justin Gleeson, Australia’s Solicitor-General and second ranking ‘law officer’ in the land. Gleeson is a ‘Senior Counsel’ — the latter-day version of a ‘Queens Counsel’. Gleeson is having a very public argument with his supervisor, Attorney-General (and Senator) George Brandis who is the nation’s ‘first law officer’. Brandis is a ‘Queens Counsel’ — better known as a QC. Apparently, the issue at the heart of the argument is Brandis decreeing that Gleeson’s office will not offer advice or counsel to anyone in the federal government (political or public servant) unless the request comes through Brandis’ office.

The ABC’s website has given us a four-act play (probably generous, it seems more like a soap opera) that describes the situation

to date. At a meeting between Brandis and Gleeson, Brandis apparently said:

… there had been a lazy practice within the Government and the public service to approach the solicitor-general requesting legal advice directly, and that his office should act as something of a gatekeeper.

Apart from the implication that a senior public servant and lawyer can’t manage his workload, why would Brandis want to know what other politicians or senior public servants need legal advice about?

It’s not the first time Brandis has attempted to influence the work of public servants in his employ. Human Rights Commissioner, Professor Gillian Triggs, conducted

an enquiry with less than flattering findings for the government into the children Australia holds in detention camps in PNG and Nauru. Brandis, through a government official, asked Triggs to resign (thus reducing the ‘severity’ of the findings) at a meeting on February 3, 2015. Triggs, when recounting the matter in a Senate Estimates Committee hearing, advised that she had rejected

the overture:

"My answer was that I have a five-year statutory position, which is designed for the president of the Human Rights Commission specifically to avoid political interference in the exercise of my tasks under the Human Rights Commission Act," she said.

Professor Triggs also testified that the secretary, Chris Moraitis, told her she would be offered another job if she did.

She described the offer as "entirely inappropriate".

Brandis claimed that he had lost confidence in Triggs as in his view:

… she had made a decision to hold the inquiry after the 2013 election and had spoken during the caretaker period, quite inappropriately, with two Labor ministers, a fact concealed from the then-opposition — I felt that the political impartiality of the commission had been fatally compromised.

"The Human Rights Commission has to be like Caesar's wife, it has to be beyond blemish."

So Brandis is suggesting because Triggs discussed a relevant issue with two politicians from the other political party during an election campaign, she should be sacked. Those of a somewhat cynical bent might suggest that conversations between senior public servants and politicians occur all the time during election campaigns despite the ‘caretaker conventions’ that are put into place: the real issue here was something else — potentially the contents of a report that rightly gained some publicity at the time for its criticism of the government’s policy. To be fair to Triggs, her office isn’t the only human rights organisation critical of Australian government refugee policy. Rationally, if the ALP government had been returned in the 2013 election, the Human Rights Commission enquiry into detained children would have reflected just as badly on the ALP as it did on the Coalition government.

In the 2014 Federal budget, Brandis oversaw significant cuts to the community legal sector. When asked if he had consulted with the sector, he claimed he did. Others in the sector claimed he didn’t. Shadow Attorney-General, Mark Dreyfus effectively invited Brandis to ‘put up or shut up’ by releasing his diary for the period where the consultation was supposed to have occurred. Brandis chose not to, so Dreyfus made a Freedom of Information request. As the

ABC reported:

The FOI was originally blocked by the Attorney-General's chief of staff, who claimed it would take hundreds of hours to process because Senator Brandis would have to personally vet each and every entry before they could be released.

Dreyfus appealed the decision to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal and won. Brandis appealed the appeal decision to the Full Court; which eventually found in Dreyfus’ favour. While Dreyfus (who is also a QC) represented himself, apparently at no cost to the taxpayer, Brandis’ legal fees came in at over $50,000 according to Dreyfus, as reported by the ABC. Even after that, the Freedom of Information request has to be reconsidered rather than released immediately.

Brandis was also the one that couldn’t move his $7,000 bookcase to hold his $13,000 worth of taxpayer-funded books and magazines from the office he was in prior to the 2013 election into the ministerial office. So a $15,000 bookcase was custom made for his

new office.

As well as being Attorney-General, Brandis has been the Minister for the Arts; maybe he likes attending the first-night performances. The Australia Council (for the Arts) was formed under the Holt Government

in 1967 and has been traditionally the vehicle whereby the Australian government funds artistic and cultural endeavours across Australia. In the 2015 federal budget, Brandis, as Arts Minister, oversaw a $110 million cut in the budget of the Australia Council to create a new arts funding body called the

National Program for Excellence in the Arts. While some who have had funding applications rejected by the Australia Council in the past may argue that that body wouldn’t know ‘arts’ if they fell over it, there is a probability that in some cases the claim is fuelled more by hurt and anger than any valid criticism of the Australia Council. Like all funding bodies, there is also potentially some internal politics to overcome that could conceivably increase the chances of a successful application ‘should the game be played correctly’.

The ABC

reported at the time:

Senator Brandis said there is a widespread perception that the Australia Council is 'a closed shop'.

'We would be blind to pretend that there aren't complaints from those who miss out, who have a perception that the Australia Council is an iron wall; that you are either inside or outside,' he said.

'I've heard that from so many people. That is particularly a perception held outside Melbourne and Sydney.'

Having said that, Brandis was proposing his new arts funding body was to be run by his ministry office, rather than by arts funding professionals. The logic that supports taking arts funding away from professionals in their field and handing it to a potentially highly politicised minister’s office is dubious at best.

What is it with Brandis? We have a person who isn’t afraid to spend taxpayer money on Quixotic endeavours such as custom made book shelves and legal appeals costing the best part of $75,000 while cutting the funding to those that assist those on little or no income through the legal system. When the funding was provided, it allowed the community legal providers to run on the proverbial ‘smell of an oily rag’.

The government rightly employs experts in their field such as Gleeson and Triggs to manage difficult and sensitive responsibilities within the government. The government also has an established bureaucracy that has significant knowledge and experience in ‘the arts’.

Yet Brandis believes that he needs to manage the Solicitor-General’s workflow, publically suggests that the reason the Human Rights Commission brings down a report challenging the government’s behaviour was to discredit the government of the day and believes his ministerial office knows more about ‘the arts’ than those with considerable demonstrated experience.

While it is a legitimate action for a government minister to make the final call when it comes to determining policy within their department, there is a difference between policy and implementation. It’s probably fair to suggest that a number of politicians on both sides of parliaments (at all three levels of government) are factional warriors; at some stage they have pledged complete loyalty to what they see to be the objectives of the political party. Rather than seeing the world through ‘rose coloured’ glasses, the world has a deep blue, red or green hue.

The problem with these people is that criticism of their chosen position is a problem. Brandis shows this by his treatment of Triggs and Gleeson – both of whom have criticised Coalition government policies or practices, Triggs with the report on children in detention camps and Gleeson has obviously given advice contrary to the wishes of Brandis. Conservatives seem to have no problem with demonstrating double standards in cutting services to others while improving their lot in life at others’ expense.

Brandis frequently chooses in media interviews to assume the ‘conservative warrior’ persona, and while his personality is not the problem of his political leader, his actions as a minister of the crown are. Setting himself up to muzzle independent experts within his department primarily because the advice doesn’t fit the Coalition’s view of the world is a dangerous precedent — and you would think that Australia’s first law officer would have a better idea of the importance of precedents. If he doesn’t, Turnbull, who is also a lawyer, should be in a position to see the problem.

This article started by looking at how sometimes various employees have to make decisions that adversely affect their employer and determined that at times these decisions were made for the greater good. It’s a pity that political warriors seem to have little understanding of the greater good.

Current rating: 0.4 / 5 | Rated 14 times