Why did Tony Abbott thrive as Leader of the Opposition, but turn out to be such a dud as Prime Minister?

What was it about his period in opposition that was so different from his period as the nation’s leader?

There are many possible answers to these questions.

This piece asserts that the most plausible reason for the difference is that in opposition he had the uncanny ability to frame the political debate in his favour, but in government that ability deserted him.

Let’s begin by defining what framing means. In common parlance, to frame something is to provide it with a surrounding; objects of art are commonly framed. A suitable frame contributes to the appeal of the object. An attractive object can be diminished, made unattractive or even repulsive if placed in a discordant frame.

In the political arena, suitable framing is crucial. It has been around in politics since time immemorial, but perhaps not well known by that name. Concepts that have a name are more easily understood simply because they are named. The name ‘framing’ makes it easier to understand what the concept means. Framing creates a perspective, an orientation, a way of viewing. Suitable framing is a winner, unsuitable a loser. Cynics diminish the concept of framing when they label it simply as ‘spin’. Framing is much more than spin. Spin conflates with misinformation.

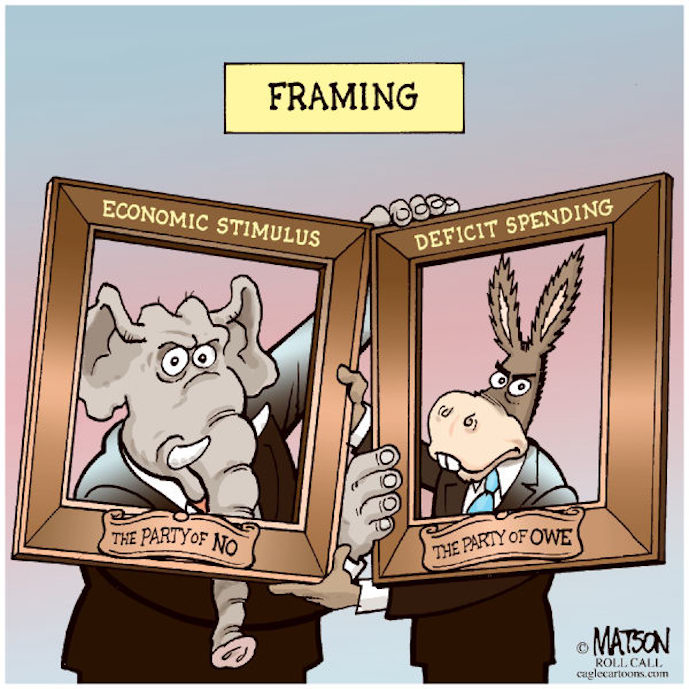

By way of illustration, let’s begin with a classic example of framing in our own federal political arena. During the global financial crisis, Labor framed the stimulus package as saving jobs, spurring economic growth and supporting communities. After the first tranche, the Coalition strongly opposed the package, framing it as needlessly running up unmanageable debt and budget deficits. The same divergent framing occurred in the United States, as the image above portrays.

George Lakoff devotes a chapter in his book

The Political Mind to the subject of framing.

He asserts that:

…”we think in terms of frames and metaphors that fit our worldviews, and language can be chosen to activate frames, metaphors and worldviews.” He goes onto say:

“Framing is not just a matter of slogans. It is a mode of thought, a mode of action, a sign of character. It is not just words, though words do have to be said over and over again.” He warns that if you accept the opponent’s frame, you are trapped.

Lakoff illustrates framing with examples drawn from the Iraq War and President George Bush’s representation of it. He describes the way he cleverly framed the debate to his advantage, and at the same time to his opponents’ disadvantage.

Here is an excerpt from Lakoff’s book:

”…the framers of the Constitution framed Congress as ‘Decider’ on any overall military strategic mission, including troop levels, general deployments, and so on. The president is the executive who has the duty to execute that overall strategic mission.

“…the president claimed that he, as commander in chief, had such powers. The president framed Congress as merely a bursar of funds for his military actions. He was reframing the Constitution.”

President Bush used memories of 9/11 to insist that Americans were subject to an ever-present terror threat. Any contrary view was framed as ‘soft on terror’. Terrified of this label, the Democrats accepted his framing and were thereby trapped.

Bush wanted to invade Iraq and so invented ‘weapons of mass destruction’, and framed the war as the pursuit of them. He deceived the Congress and the people about the evidence for their existence. The Democrats went along with his frame. When weapons of mass destruction failed to eventuate, Bush re-framed the war as a ‘rescue mission’, to rescue the Iraqi people from the tyrant Saddam Hussein.

He eventually declared the war was over; his army had defeated Hussein’s army. But he continued to frame himself as a ‘war president’ to keep the war frame alive. The Democrats continued to accept Bush’s war frame. He continued to frame himself as the sole ‘decider’ on military action and Congress as merely the funder of the actions he ordained.

After Bush declared the war was over, the US military personnel in Iraq then became an occupying force. Like its predecessor, it required continuing funding by Congress. Any attempt by the Democrats to limit Bush’s military options, or to shorten the war by tying funding to the steady withdrawal of troops, was framed by him as ‘putting our troops in harm’s way’ through inadequate funding, or as abandoning US troops in a faraway place.

Whichever way Bush framed the Iraq situation, the Democrats remained trapped in his framing. They were seemingly incapable of re-framing the debate. They could have framed Bush as usurping the Constitution and the power and responsibility it gave to Congress; they could have framed themselves as defenders of the Constitution and Bush as a traitor trying to overthrow the Constitution. But they were afraid, fearful that any failure in Iraq would be pinned on them. They lost the opportunity to reframe the situation in a way that favoured them. It takes courage to reframe when your opponent has the upper hand in framing.

Tony Abbott’s framing began almost on the day he became Leader of the Opposition.

Abbott, or was it Peta Credlin, believed that if the emissions trading scheme proposed by Kevin Rudd, (which Malcolm Turnbull was inclined to accept until his party voted him out of leadership in favour of Tony Abbott), was framed as a ‘Carbon Tax’, a ‘Great Big New Tax on Everything’, it would resonate stridently with the electorate, which is never disposed to accept gladly any new tax. Framing the ETS as ‘a carbon tax’ was an immediate success. It was embellished as Coalition members pointed out that the ‘carbon tax’ would increase the cost of everything: opening the fridge, using the iron, vacuuming, watching TV. Barnaby Joyce extravagantly predicted that the cost of a lamb roast would rise to $100 because of the carbon tax. And of course this evil tax would wipe Whyalla off the map!

Eventually Julia Gillard tacitly accepted that the ETS was a ‘tax’, and having told the electorate: ‘There will no carbon tax under a government I lead…’, she lost credibility and authority. Polls showed that the electorate did not want a new tax, and when Abbott promised that its abolition would be his first act after election, the people embraced his framing and accepted his solution.

When the ‘carbon tax’ was cleverly linked to another, ‘the mining tax’, the strength of the framing was increased. ‘Axe the tax’ became an appealing slogan that applied to both. Soon others were echoing it; even Gina Rinehart and Twiggy Forrest took to the hustings to rail against the mining tax, which they hinted would kill off their mining ventures. The framing worked a treat.

Abbott successfully framed another contentious issue – the arrival of asylum seekers by boat from Indonesia and beyond. He accentuated John Howard’s line: ”We will decide who comes to this country and the manner of their arrival”. He gave asylum seekers a pejorative label: ‘illegals’, although they were not. He represented them as illegally thrusting themselves into our country, and it wasn’t long before they were viewed as taking Australian jobs and living on our social welfare. Some in the media even accused the Gillard government of putting them up in flash hotels. Resentment was fostered. For voters of a more humanitarian inclination, the harsh approach to these asylum seekers was softened by another framing strategy, namely that the government wanted this illegal trade in people smuggling stopped to avoid drownings at sea. It was a pseudo-humanitarian framing, but it worked. Coupled with ‘We will stop the boats’, it had great appeal with much of the electorate, especially in the marginal seats in Western Sydney. ‘Stop the boats’ became one of Abbott’s most powerful three word slogans.

Over time the framing morphed into one of ‘border protection’ and in government Abbott created the ‘sovereign borders’ frame, likening the asylum seeker-carrying boats to an invasion force to be repelled by the re-badged and well-funded Operation Sovereign Borders, which operated with military precision and all the secrecy of a military operation in a theatre of war. Every step reinforced the framing of asylum seekers as ‘the enemy’ to be repulsed, rather than desperate displaced people seeking asylum from persecution. Labor was framed as supporting the arrival of the boats. Scott Morrison repeated endlessly that Labor wanted to ‘put sugar on the table’, an apparently irresistible invitation to people smugglers and their cargo. For its part Labor, scared witless of being tagged ‘soft on border protection’, went along with Abbott’s framing, seemingly unable to counter it without being seen as soft and unable to ‘protect’ Australia from this invading force.

Abbott’s framing went far beyond the political issues of the day; he fashioned his framing so that it became a deeply personal attack on his opponent, Julia Gillard, one that questioned her integrity as well as her competence. Remember: 'Juliar', 'Bob Brown's bitch' and ‘Ditch the witch’. His discrediting of her as untrustworthy reached a crescendo with: ‘Her father died of shame’; in other words, even her father disowned her. Despite her famous riposte, her misogyny speech that framed Abbott as a mean and nasty misogynist, which resonated so strongly with female but not male voters, Abbott’s framing of Gillard built up resentment towards her among the voters, and eventually dislike. It succeeded so well that her poll status fell to the point that even her colleagues concluded she could not win the upcoming election, and replaced her with Kevin Rudd.

Abbott’s framing went far beyond the political issues of the day; he fashioned his framing so that it became a deeply personal attack on his opponent, Julia Gillard, one that questioned her integrity as well as her competence. Remember: 'Juliar', 'Bob Brown's bitch' and ‘Ditch the witch’. His discrediting of her as untrustworthy reached a crescendo with: ‘Her father died of shame’; in other words, even her father disowned her. Despite her famous riposte, her misogyny speech that framed Abbott as a mean and nasty misogynist, which resonated so strongly with female but not male voters, Abbott’s framing of Gillard built up resentment towards her among the voters, and eventually dislike. It succeeded so well that her poll status fell to the point that even her colleagues concluded she could not win the upcoming election, and replaced her with Kevin Rudd.

This brings to an end the first part in this short series on political framing. I trust that I have explained the concept of framing, and that the illustrations drawn from the American context at the time of the Iraq conflict, and the local illustrations drawn mainly from previous periods in the Australian electoral cycle have exemplified the concept of framing.

This brings to an end the first part in this short series on political framing. I trust that I have explained the concept of framing, and that the illustrations drawn from the American context at the time of the Iraq conflict, and the local illustrations drawn mainly from previous periods in the Australian electoral cycle have exemplified the concept of framing.

In the next piece, I will use more recent illustrations from our federal scene. Believe me, political framing is alive and well. Conservatives seem to have an aptitude that progressives have been unable to match. There are reasons for this. Until and unless Labor can match the Coalition’s framing, unless Labor can construct its own powerful frames, unless Labor can at least avoid becoming trapped in the Coalition’s frames, it will struggle to gain support in the electorate, especially now that the highly unpopular Abbott has been replaced by the silver-tongued, urbane and persuasive Malcolm Turnbull.

What do you think?

Ad astra invites us to view the utterances of politicians through the prism of ‘framing’. What are they trying to say? What impressions are they trying to create? In what way do they seek to change our opinions? He uses examples from here and overseas to illustrate political framing.

In part 2 he will use examples from a previous electoral cycle. You will immediately recognize them.

Current rating: 0.6 / 5 | Rated 17 times