In the first of this short series on framing:

Framing the political debate – the key to winning, I described the concept of political framing as developed by cognitive scientist and linguist George Lakoff, which he described in his book

The Political Mind. I illustrated it with examples drawn from the Iraq war and from our federal political scene. This piece draws on more recent examples of how framing has been used successfully, principally by the Coalition government. Conservatives have an aptitude in selecting frames for the policies and plans they wish to introduce. Often they are winners; occasionally though their frames turn out to be losers.

Leading up to the 2013 election Tony Abbott embraced three memorable slogans: He promised he would “Abolish the carbon tax’, ‘Stop the Boats’, and ‘Repay the Debt’. He embellished these with more negatives: ‘This toxic tax’, ‘The World’s Biggest Carbon Tax’, ‘Axe the Tax’, ‘Stop the waste’, and a positive: ‘Hope, Reward, Opportunity’. Someone must have persuaded him that three words slogans would stick in voters’ minds. And they did. All of these were frames. They framed Labor as a high taxing party, wasteful of taxpayers’ money, running up intolerable debt and huge budget deficits, and unable to protect our borders, all negatives. The Coalition framed itself as the party that would fix Labor’s mess, and it also offered hope, reward and opportunity, all positives. Very simple, yet successful!

When Joe Hockey entered the framing arena, he thought he was on a winner when he coined the slogan: “

The age of entitlement is over”. He still boasts of the address he delivered in London on that theme. He framed those whom he deemed dependent on welfare entitlements as ‘leaners’, a pejorative tag that he used to contrast them with the ‘lifters’, the good guys who pulled their weight, and whose taxes supported the lazy leaners. This framing appealed particularly to conservatives, many of whom believe that those who earn a lot deserve it, and are entitled to keep it; those with little deserve to be poor. Hockey reinforced his framing by publicising how many dollars from their salaries various hardworking lifters contributed to supporting the leaners.

Although progressives disliked his framing, his supporters applauded. But when Hockey framed his 2014 budget along those lines he came unstuck. It penalized his designated ‘leaners’, those on the aged pension and on welfare, by extracting from them the savings he insisted he must make to balance the budget, while scarcely touching those on higher incomes. The electorate erupted with disgust. Voters, even Coalition supporters, saw the budget as grossly unfair, penalising as it did those least able to afford it.

Hockey’s framing, and we know it was Abbott’s too, backfired badly. Faulty framing is as damaging as excellent framing is beneficial. Soon Hockey, Abbott and Cormann were forced into retreat. So damaging was this framing that they reversed it in the 2015 budget.

Another striking example of implausible framing was the representation of Labor as incompetent money managers and profligate spenders, running up appalling debts that our grandchildren will still be repaying. So determined was Abbott to frame Labor as bungling spendthrifts, that he deliberately inflated the debt levels, painted a picture of never ceasing debt spiralling out of control, and budget deficits stretching out ‘as far as the eye can see’. He boasted that the adults in the Coalition would soon pay off the debt, and get the budget back to surplus. He framed the situation as being a ‘debt and deficit disaster’ and an ominous ‘budget emergency’. Initially, the electorate believed his inflated rhetoric until it became obvious, even to his supporters, that the debt and deficit was steadily worsening under his own government’s stewardship. By the 2015 budget, although the fiscal situation had deteriorated further, voters noticed that the ‘crisis’, the ‘disaster’ and the ‘emergency’ had magically disappeared.

Abbott’s stocks had been poor almost since his election, and continued to fall with the first leadership spill. It was then that he tried to reframe his government’s performance with his astonishing: “

Good government starts today”! Even as his position continued to deteriorate until he was finally removed, he kept on with the fictitious framing of a government doing well and achieving a lot since being elected, despite his inability to get a raft of his crucial bills through the Senate. His framing was out of touch with the stark reality of a floundering, incompetent government that did not know where it was going. For framing to work it has at least to be vaguely consistent with the observable facts.

Abbott and Hockey, still smarting from the reaction of the electorate to the 2014 budget, thought they had better frame the 2015 budget differently. So they framed it as a ‘have a go’ budget:

"So now is the time for all Australians to get out there and have a go." After castigating those on welfare in 2014, they were now jollying us all to ‘have a go’. The electorate could not fail to notice the complete turn around in rhetoric. How many realized that this about turn was simply a reframing? They dropped the pejorative ‘emergency’ frame and installed the benign ‘have a go’ frame. No doubt they hoped nobody would notice their back flip, but of course both the commentators and the voters did.

Once Malcolm Turnbull became prime minister we saw entirely new framing, although his policies look strikingly similar to Abbott’s. His framing was upbeat:

”There has never been a more exciting time to be an Australian…We have to recognise that the disruption that we see driven by technology, the change is our friend if we are agile and smart enough to take advantage of it. There has never been a more exciting time to be alive than today …”

This optimistic framing appealed to the electorate after years of negative framing by Abbott, who was always telling us of the threats we faced, from terrorists, from asylum seekers, from budget crises, from the leaners who were draining the coffers dry. Turnbull’s ratings, and those of the Coalition, soared, so relieved was the electorate to see Abbott’s negative framing replaced by Turnbull’s positive, buoyant framing. Whether Turnbull can deliver remains to be seen, but what is obvious is that voters prefer upbeat rather than downbeat framing, and are prepared to give the optimist a go.

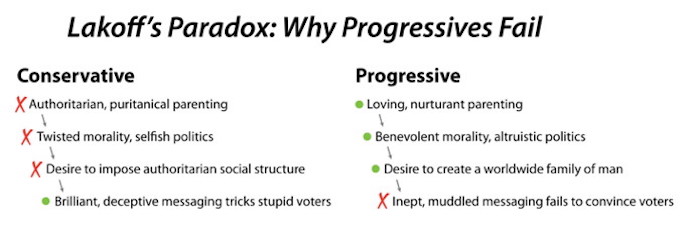

Let’s look now at how Labor responded to the Abbott/Hockey framing. Lakoff believes that progressives the world over are less skilful at framing appealing messages because of their parental upbringing, as detailed in

Understanding the conservative mind. His concepts are summarised below.

Lakoff attributes progressives’ lack of skill in framing to their embrace of what he terms: ‘Old Enlightenment thinking’, which posits that the facts should speak for themselves and that they can win elections by citing facts and offering programs that serve voters’ interests. Progressives believe: ‘Give the voters the facts, explain what they mean with persuasive reasoning, propose policies that serve their interests, and all will be well. The people will understand once policies are explained to them.’

It is curious that progressives have been so slow to work out that this is not so. Facts and logic are insufficient. Emotional intelligence has to be integrated into the frame to convince the voter. Abbott appealed to the emotions with his use of negative words. They brought about the desired adverse emotional reaction. Words such as tax, debt, deficit, crisis, emergency, terrorism, and phrases such as being overrun with ‘invaders’, evoke fear reactions. Having created fear, Abbott promised to soothe those fears, protect the people and our borders, and fix the fiscal mess left by Labor.

In contrast, positive words: ‘exciting times’, ‘opportunity’, or even ‘have a go’, result in a positive emotional response from voters. Yet Labor was never able to come up with positive frames that negated Abbott’s negative ones. Since the debt and the deficit were hardly trivial, it proved impossible for Labor to pass them off as a temporary aberration that would correct itself in the fullness of time, although several sound economists were sanguine about the deficit and its eventual correction. Abbott framed debt and deficit as a disaster, and it stayed that way in voters’ minds.

Neither was Labor able to counter effectively Abbott’s rhetoric about asylum seekers and boat people. Any semblance of a more humane attitude was negated by: ‘Labor is soft on terror’. Note that ‘terror’ and ‘asylum seekers’ were conflated in this framing, although there is no credible evidence that boat people seeking asylum are, or would become terrorists. Moreover, Morrison accused Labor of virtually inviting people smugglers to bring more asylum seekers by ‘putting sugar on the table’. The Coalition’s framing always outmaneuvered Labor’s.

The best Labor was able to come up with were what some journalists mockingly tagged ‘Bill Shorten’s zingers’.

Lakoff writes extensively about ‘fear of framing’, which he defines as “

…a fear of how the other side will frame your vote, and a fear of framing the truth on your own.” He went onto say:

Framing the truth so that it can be understood is not just central to honest, effective politics. It is central to every aspect of human life. It takes knowledge and honesty, skill and courage. It is part of being a full human being. It is not just the province of political leaders; it is the duty of a citizen.

Fear of framing is debilitating, not just to you, but to everyone who depends on you.

Labor ought to read what Lakoff says and lift its game.

He goes onto discuss the difficult process of what he describes as ‘getting unframed’. Here is a striking example of how Barack Obama unframed a question posed by TV journalist Wolf Spitzer in a Democratic presidential debate on

CNN in 2007. Lakoff describes Spitzer’s behaviour in this debate as “

…a wolf in sheep’s clothing – a conservative who poses as a neutral journalist. All through the debate he used conservatives frames. Some candidates managed to shift the frame to their ground, but all too often they tried to answer and were trapped in a conservative frame. This led up to one of the greatest political moments in recent political television”.

The context included the contentious argument about what language US citizens should speak. Many immigrants do not speak English.

Spitzer: I want you to raise your hand if you believe English should be the official language of the United States.

Barack Obama refused to take it anymore. He got up, stepped forward, and said:

Obama: This is the kind of question that is designed precisely to divide us. You know, you’re right. Everybody is going to learn to speak English if they live in this country. The issue is not whether or not future generations of immigrants are going to learn English. The question is: how can we come up with both a legal and sensible immigration policy? And when we are distracted by these kinds of questions, I think we do a disservice to the American people.

Lakoff relates how he cheered Obama’s response. He goes onto say: “

The first lesson about the use of framing in politics is not to accept the other side’s framing. One part of that is politely shifting the frame, as Obama did. “You know, you’re right…” But there are situations like presidential debates where the host should not be allowed to get away with conservative bias via framing. Obama did it just right, challenging the question itself. His response could be taken as a mantra: “This is the kind of question that is designed precisely to divide us.”

You will recall how Tony Abbott designed the frame ‘Team Australia’ for the same purpose: precisely to divide us.

Labor and its leaders need to become more proficient in the framing arena. They should not allow themselves to be trapped in their opponents’ frames. They must become more adept at challenging these frames, calling them out, as did Obama. They must become more creative and skilful in developing their own frames.

Unless they can unframe their opponents; unless they create powerful frames that represent their point of view, their values, their policies and their plans, they are destined to wallow in the wake of Coalition frames.

And they have to understand that facts and reason alone are insufficient. Unless the emotional content of their frames is designed to appeal to the voters, they will not succeed in attracting the swinging voters they need.

The last in this brief series on framing, which will be published in a couple of days, uses contemporary examples of how the government is framing its ideas, policies and plans. Some are, or will be effective; some will have limited appeal; some may end up on the scrap heap. Labor’s will need to counter them, match them, or surpass them. That’s quite a challenge.

What do you think?

Ad astra has used examples from our own political scene to illustrate further the concept of framing. You will have recognized many of them. He illustrated the danger of becoming trapped in an opponent’s framing, and how to disentangle from it.

In part 3, he will use very contemporary examples of framing which you will remember.

Current rating: 0.6 / 5 | Rated 17 times